my hypercinema-final can very well be considered as my icm-final too (see final-project-log).

however, matt & i had committed to making our icm-finals together, and i couldn’t say no.

both of us had overlaps of interest in computational letterforms. we met, and came up with something that was intellectually interesting to us.

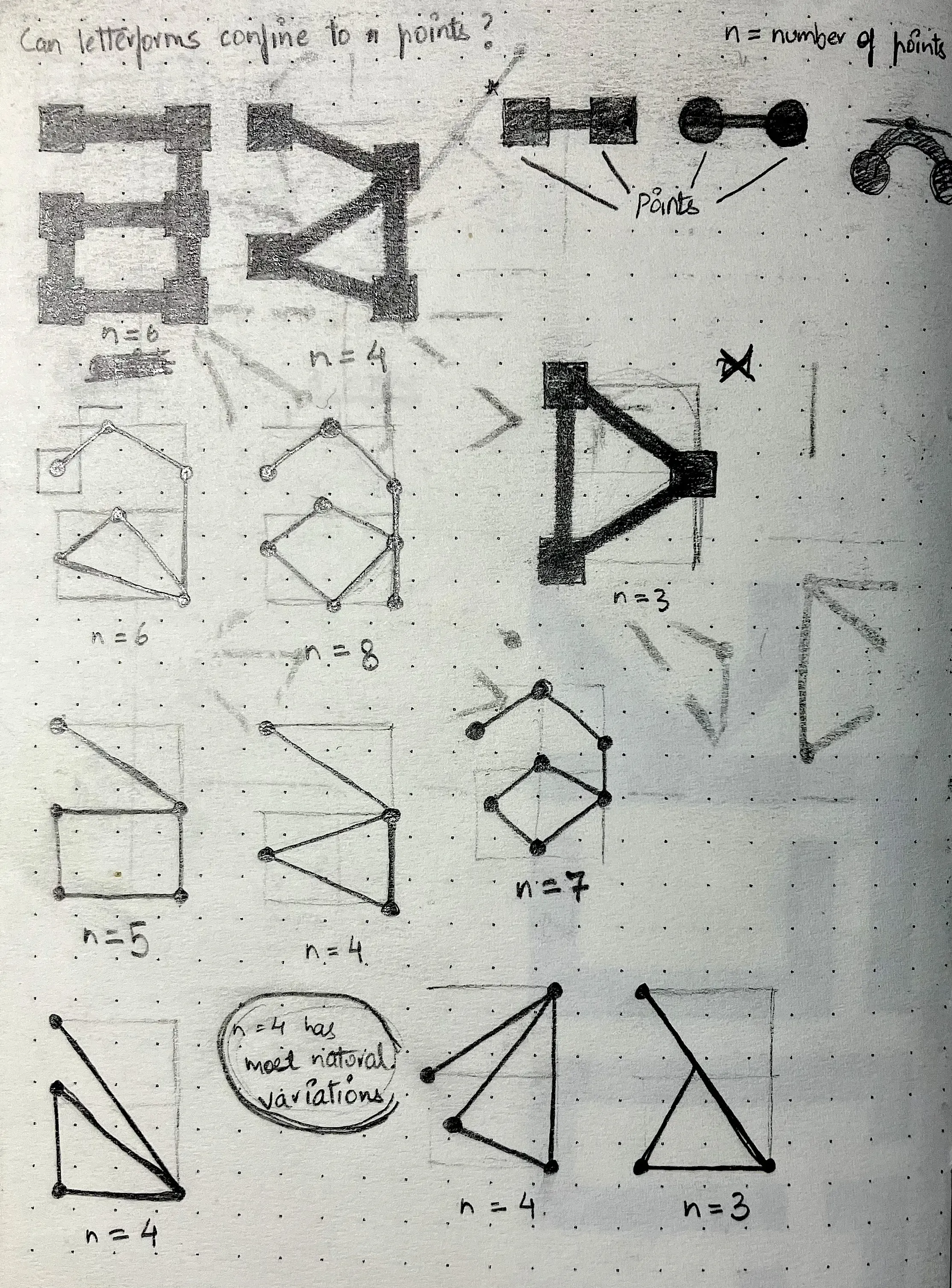

we took my earlier n=4 explorations as a base, where i had imagined letterforms as a mere set of rules, and used computation to change their visual form over time.

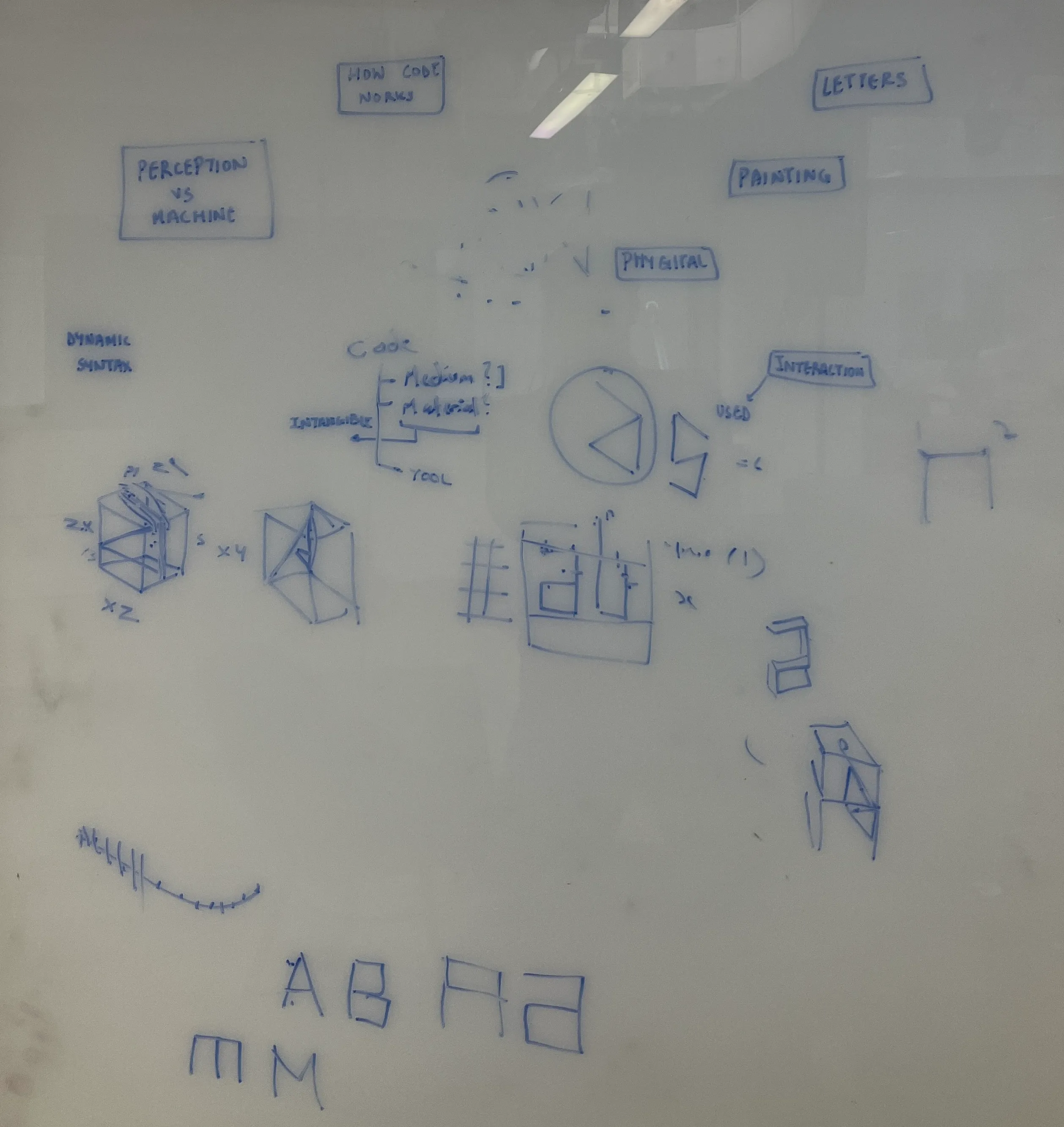

old notes from that project:

![]()

![]()

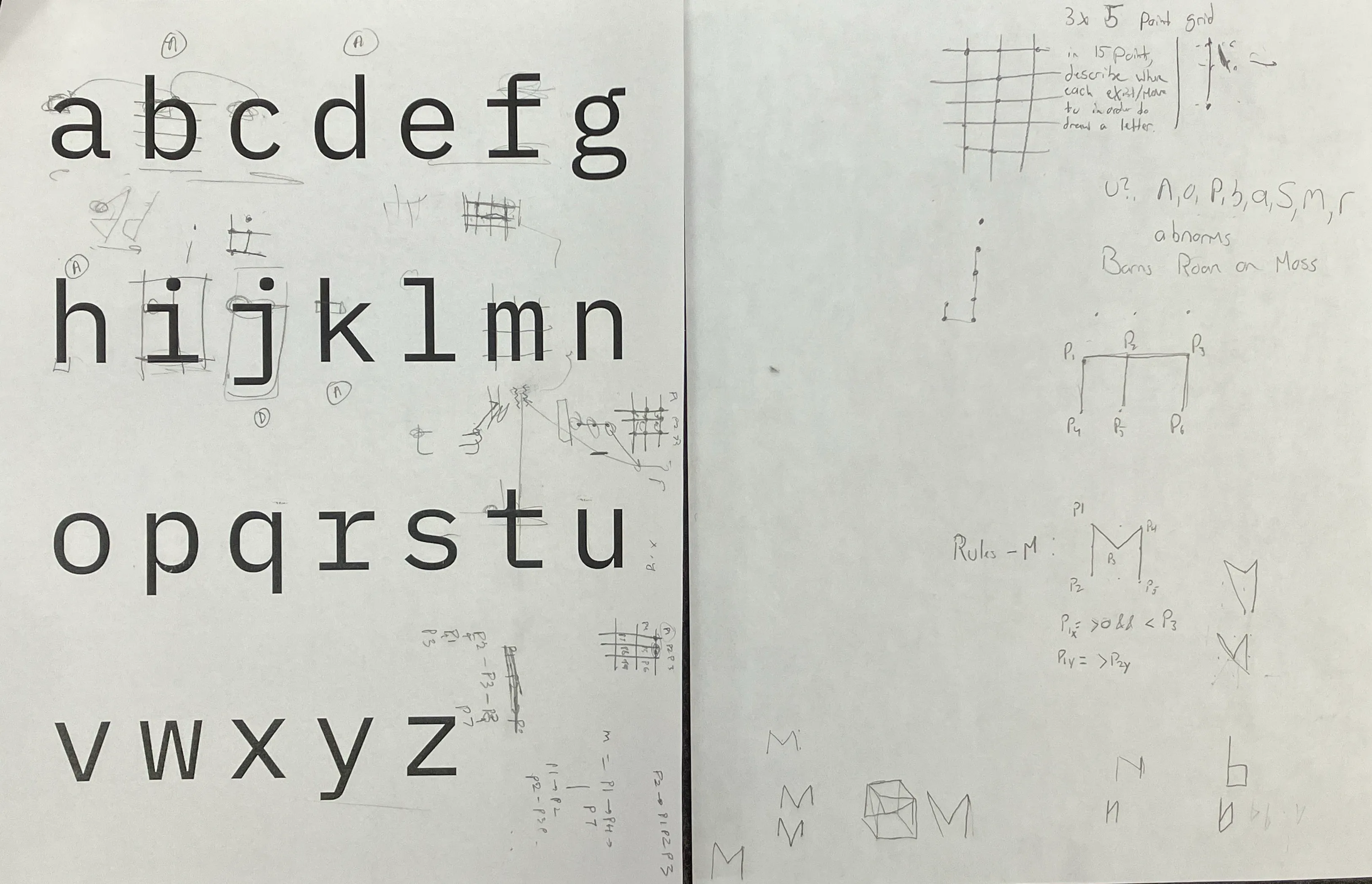

matt & i worked together to think what would happen if we completed that initial enquiry (with all letterforms), and somehow spatially represent them (like peter cho’s spatially represented letterforms i originally saw here).

however, when i saw mimi’s talk at movement-lab, barnard, i knew that matt & i got overly excited with our initial enquiry, and would, perhaps not do justice to mimi’s philosophy of playing with perception & feeling. while i knew this, i still decided to go with it; because of these lines in the brief:

scratch a new itch

How did coding it make the final product different from using software?

and in pursuit of this:

Did coding it reveal something to you?

sadly, i did not have as much time as i would have liked, because i was focused on finishing my physical-computing-final (see final-project-2_log) and hypercinema-final (see final-project-log).

matt made something amazing for the first sketch. i looked at his code, and it seemed too complex to understand with a cursory reading. so, i explored something he hadn’t in his sketch — letting lettforms morph in the third-dimension.

code:

/* mimi's ask:

Discover something!

You can take something you did earlier this semester and expand it. You can scratch a new itch. You can make a Frankenstein project by combining earlier code. And yes you can present the coding portion of your PComp final so long as you can speak to how you applied computational thinking to shape the project.

What do you find interesting about what you did?

How did coding it make the final product different from using software?

Did coding it reveal something to you?

*/

/*

matt & i want to make spatially represented typography that evolves over time. computation is the only way to do it, simply because so many patterns exist. and, latin letters seem to be constructed with rules; but they're not usually thought of as that way.

*/

/*

i looked at what matt did, and wondered how i could contribute in the limited time i had. so, i played with 3-d space.

*/

/*

a letterform is made with vertices in order.

*/

let letterforms = [];

function setup() {

createCanvas(1000, 1000, WEBGL);

let feed_points = [

{

x: 100,

y: 100,

},

{

x: 200,

y: 100,

},

{

x: 300,

y: 100,

},

{

x: 300,

y: 200,

},

{

x: 200,

y: 200,

},

{

x: 100,

y: 200,

},

{

x: 100,

y: 300,

},

{

x: 200,

y: 300,

},

{

x: 300,

y: 300,

},

{

x: 300,

y: 200,

},

];

console.log(feed_points);

letterforms[0] = new Letterform(feed_points, 0);

}

function draw() {

background(0);

push();

translate(-width / 2, -height / 2, 0); //translate back to 0,0

for (let letterform of letterforms) {

letterform.display();

letterform.move();

}

pop();

if (frameCount % 60 == 0) {

//select a random point.

let n = floor(random(letterforms[0].points.length));

letterforms[0].new_z[n] = random(-100,100);

}

}

class Letterform {

constructor(points, anchor) {

this.points = points;

this.origin_x = [];

this.origin_y = [];

this.origin_z = [];

this.current_x = [];

this.current_y = [];

this.current_z = [];

this.new_x = [];

this.new_y = [];

this.new_z = [];

for (let i = 0; i < this.points.length; i++) {

//set all to defaults received in construcion-points.

this.origin_x.push(this.points[i].x);

this.origin_y.push(this.points[i].y);

this.origin_z.push(0);

this.current_x.push(this.points[i].x);

this.current_y.push(this.points[i].y);

this.current_z.push(0);

this.new_x.push(this.points[i].x);

this.new_y.push(this.points[i].y);

this.new_z.push(0);

}

this.anchor = {

x: this.points[anchor].x,

y: this.points[anchor].y,

};

}

display() {

stroke(255);

strokeWeight(2);

// beginShape(POINTS);

for (let i = 0; i < this.points.length-1; i++) {

strokeWeight(10);

point(this.current_x[i], this.current_y[i], this.current_z[i]);

strokeWeight (2);

line(this.current_x[i], this.current_y[i], this.current_z[i], this.current_x[i + 1], this.current_y[i + 1], this.current_z[i + 1]);

}

// endShape();

}

move() {

for (let i = 0; i < this.current_z.length; i++) {

this.current_z[i] = lerp(this.current_z[i], this.new_z[i], 0.1);

}

}

}

matt & i had to do a bunch of 3-d thinking to get the cursor to line up with the way text is rotated in 3-d space.

whenever we got stuck on a problem, i could see matt try to come up with the most efficient solution. i instead would put together scrappy prototypes. we stumbled upon this difference during itp-winter-show-2025 poster design too.

when we spoke about it, we realised that it comes from our difference in how we’ve grown up to use code. he always thinks of the most efficient way (which is why i, sometimes, cannot understand the code he writes), and i think of the easiest way to achieve the desired thing (and he cannot understand why i may have used what i use (for example multiple transformations instead of one (which he would attempt to do))).

i made him a sketch to understand 3-d transformations:

let objs = [];

function setup() {

createCanvas(400, 400, WEBGL);

angleMode (DEGREES);

}

function draw() {

background(0);

for (let ob of objs) {

ob.display();

}

}

function keyPressed() {

let x = mouseX;

let y = mouseY;

let z = 0;

objs.push(new Obj(x, y, z));

}

class Obj {

constructor(x, y, z) {

this.x = x;

this.y = y;

this.z = z;

this.r = random(0,90);

this.axis = random (3);

this.ang = 45;

}

display() {

fill(255);

push();

if (this.axis < 1){

rotateX (this.ang);

}

else if (this.axis < 2){

rotateY (this.ang);

}else{

rotateZ (this.ang);

}

rect(this.x, this.y, 50, 50);

pop();

}

}

output:

mimi said that this exploration was meaningful. that was interesting: to reveal meaning of things over time. i’m too tired to reflect on this properly, but i shall; once winter-break resumes.